Kampala, Uganda | By Timothy Kalyegira | When 2011 started, all eyes and ears were focused on the general election, particularly the presidential election.

Both local and foreign media analyzed and reported the campaigns and the actual election as the biggest story of the year and in the local media countdowns had been observed for months leading up to the date when “Uganda decides”.

As matters stand now, February 18, 2011 seems so long ago, almost as if it were a date from last year, not 2011.

The reason the election, President Museveni’s “Another Rap” campaign song, the huge sums of money spent, the heavy police and military deployment before the election, the election’s outcome and the bitter reaction by the opposition now seem so far away is because Uganda is facing the really big news story of 2011.

This big story of 2011, which might prove to be the biggest story of the year, is the national economic crisis.

There are many Ugandans who find politics boring, petty or irritating. There are deep disagreements within some families over whom to support. It is the subject of constant debate on radio and in the newspapers.

But there is nothing quite as concrete in terms of how it affects people of all walks of life, in total at least 99 percent of the Ugandan population, as the economy.

2011 is the year that the Uganda shilling, by late September, had reached 2,900 units to the U.S. dollar, the lowest it has ever sunk in Uganda’s entire history, including history before independence.

It might have to be noted that the 2,900 shillings we quote is actually the shilling as it is after two zeros were knocked off during the currency conversion in 1987 and a 30 percent conversion tax levied.

So in real terms, the shilling today is at 290,000 to the dollar, making Uganda look a little like Zimbabwe.

2011 is the year that saw more electricity blackouts lasting longer, in more towns in Uganda than any year since independence.

2011 is the year that the price of a kilo of sugar reached 7,500 shillings, sold an average of 7,000 shillings and at this price, was the most expensive it has ever been in Ugandan history.

2011 is the year that school fees and university tuition fees reached their highest that Uganda has ever seen, leaving students at Makerere University no choice but go on strike.

2011 is the year that saw inflation record 21.4 percent, the highest in Ugandan history. In 2011, a sack of charcoal sold mostly for 70,000 shillings and in some parts of the country sold for 90,000 shillings.

The high cost of charcoal meant that for the first time ever, it actually has become cheaper to cook using gas — once viewed as a rich man’s luxury — than to use charcoal.

The crisis in the economy got to the point where that President Museveni, on a visit to India, was forced to issue directives from the Indian capital New Delhi ordering factories not to sell sugar to any politicians whom, the president said, were hoarding it or exploiting the market.

2011, then, is the year it can safely be said was one of the most difficult that ordinary Ugandans have ever had to go through.

The only tougher years have been 1979 and 1980 following the Tanzania-Uganda war and 1976 and the early part of 1977 when a western-led economic boycott and sabotage by anti-Amin guerrillas started to cripple the economy.

Another difficult year was 1987 in the months following the currency conversion.

Given the current economic difficulties in Uganda, it would be interesting to see what an opinion poll would reveal about President Museveni’s popularity if it were carried out today.

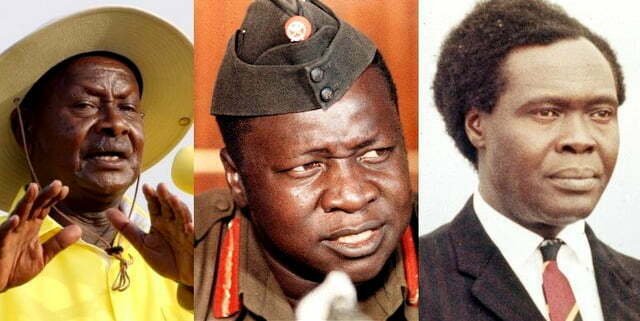

In a certain sense, the current economic crisis will end up as history’s way of vindicating both Idi Amin and Milton Obote who have been vilified since 1986 as having destroyed Uganda’s economy.

The economy under Amin

All through the 1970s under the watch of Amin, the Uganda shilling officially traded at between seven shillings and 7.50 shillings to the U.S dollar and was at 16 shillings at the then illegal black market rate.

“The high price of coffee on the world market left Uganda with a budget surplus in 1977, the first in several years,” recorded Compton’s Encyclopedia Yearbook, 1979, in an article on Uganda in 1977.

It would require a lot of research and faith to find a single year since 1986 that Uganda has actually registered a financial surplus of any kind, whether in terms of the national budget or in its international balance of payments accounts.

By contrast, the now-defunct Ugandan newsletter The Shariat commented in its February 12, 1991 edition that “Many people in the country are not at all happy with the performance of NRM government especially on the economy. Millions of people are forced to wear old clothes thrown away by the rich in Europe and America. Millions of parents have no money to educate their children. This was not the case before N.R.A captured power.”

This commentary was published in 1991 at a time when most national and international opinion was that Uganda’s economy was resurrecting after the “dark days” of Amin and Obote.

At the time The Shariat said “millions of parents have no money to educate their children,” Makerere University still offered free education for all its students. It can only be imagined how much more difficult times now are 20 years later for most parents.

Responding to one of my articles on Amin in the Daily Monitor in 2007, a Ugandan called Richard N. Kiwanuka, recalled his experience of Uganda’s social services in an email dated April 6, 2007:

“I lived in Entebbe as a little boy during Amin’s time. In 1978 I was admitted at Entebbe [Grade A] Hospital. This was the daily menu for the patients: Breakfast: bread with margarine (patient’s choice between milk and black tea.) Sugar included. Lunch: matooke, rice, posho with beef and or beans. (Well fried) Dinner: matooke, rice, posho with beef and or beans…”

Needless to say, there is no government hospital in any part of Uganda today that can claim to give its patients that kind of diet. Grade A Hospital was, if anything, taken over by State House last month for “security reasons”.

In an article in the Weekly Review magazine of Kenya in April 1975, Dr. Irving Gershenberg, Professor of Economics at the University of Nairobi assessed the Ugandan economy’s performance in the four years of Amin’s rule.

Wrote Gershenberg in the article titled “Uganda No Worse off Today”: “There is little basis for concluding that Uganda’s economy is on the brink of chaos; to the extent that weaknesses can be discerned in the economy since Amin’s takeover, such weaknesses have been limited to the more industrialised, modern sectors. The vast majority of the population are involved in agriculture, and many, in real terms, have been enhancing their economic position, if ever so slowly.”

The economy under Obote II

Other than Amin, the late former president Milton Obote is also blamed by many Ugandans and international analysts for having destroyed Uganda’s economy between 1980 and 1985 when he was ousted once again in a military coup.

Compton’s Encyclopedia, Yearbook of 1985, reviewing the events of 1984 in Uganda had this analysis of Uganda’s economy in 1984, the year most people say was Uganda’s lowest economic point of the 1980s:

“Pres. Milton Obote, in his role as minister of finance, announced in June 1984 that Uganda had achieved a balance of payments surplus for the first time in more than ten years. There had been a growth rate of 5% for the previous two years. On the strength of the improvement the government was able to merge the two-tier foreign-exchange rate [Window One, Window Two] that had been introduced two years earlier at the insistence of the International Monetary Fund…A considerable increase in tea production was also reassuring…”

So while the Amin government in 1977 recorded a national budget surplus, the second Obote government (more commonly referred to in Uganda as Obote II) recorded a balance of payments surplus for the first time since 1973.

By the early to mid 1980s, of course, Uganda still had government-owned companies like Uganda Airlines, Uganda Railways, Lit Marketing Board, Coffee Marketing Board, United Garments Industries Limited (UGIL), Produce Marketing Board, Uganda Ports and Telecommunications Corporation, Uganda Commercial Bank, the Cooperative Bank, and dozens of others that have since been sold off.

Even where many of these companies might have had their inefficiencies, the money they generated and the jobs they provided all worked to benefit the local economy. The various Uganda Airlines offices at airfields in various parts of the country provided jobs and services, as did the airline’s offices in the rest of Africa, Europe and the Middle East.

This then is a rough sketch of the Ugandan economy as it is today and was in the past. Today, there appears to be competition, a wide variety of goods and services to choose from, an atmosphere of radio and newspaper advertisements and billboards and corporate logos visible in almost every direction in Uganda’s major towns.

Many observers who interpret this to mean that Uganda’s economy is now at its best ever cannot be fully blamed for that opinion.

However, the most telling evidence of the hollowness of this can be learnt from the media. Most newspaper editors and publishers will agree and state the fact that despite this image of a vibrant private sector, the largest advertiser in Uganda still remains the Uganda government.

Not the telecoms and drinks companies or banks, supermarkets and airlines, but the Uganda government.

If the Uganda government, having divested itself of so many companies it once owned and operating in a largely privatized economy can still be the largest source of advertising revenue for the print and broadcast media, we can only imagine how much more it was before privatization.

It leads us to a question: where does all the money in handsome profits made by the foreign companies operating in Uganda go? It is taken out of the economy back to their home base.

All this might explain why most people seem to own mobile phones, there seem to be so many cars in Uganda, a wide variety of TV and radio stations to tune into, and the feeling of a vibrant economy; yet at the same time, more people seem to complain about hard economic times than ever before.