Kampala, Uganda | By Timothy Kalyegira | Over the last 20 years or so, various political actors once intimately associated with the National Resistance Movement (NRM) government of President Yoweri Museveni have fallen out with it.

All were involved in the creation or enforcement of laws or the working out of political arrangements with the NRM that appeared advantageous to the country and to them personally, but which they later came to regret and which laws and precedents that they were a part of later came to curb their freedom.

Paulo Ssemogerere

The NRM had fought a five-year civil war on the argument that the 1980 elections were rigged and it was dedicated to the restoration of democracy and the rule of law.

The NRM claimed in 1986 that the main cause of Uganda’s years of political instability was the political parties and the sectarian way by which they played on ethnic and religious sentiment to gain power or advantage.

Therefore, to break this historical pattern, political party activities should be suspended for four years to give the country time to heal, after which point a new dispensation would have emerged in which politics would now be based on principle rather than on religion or tribe.

One main political party at the time, the DP, disagreed with the ban on parties. But it was not in a position in 1986 to dictate terms to the militarily victorious NRM, and so it agreed to the ban.

Several leading DP figures were given cabinet posts in the NRM government, which made it easier for the DP to accept the new arrangement.

The former ruling party, the Uganda People’s Congress, UPC, disagreed too and unlike the DP refused to join in the NRM government, although a few UPC leaders joined the NRM against their party’s advice.

When the NRM came into power, it was militarily strong but politically weak. It lacked a large political following across Uganda in the traditional way the DP and UPC had since independence.

The support that the DP lent the NRM helped the NRM gain political legitimacy and consolidate its hold on power in the early years.

In 1995, nine years later, Paulo Ssemogerere the DP leader announced he was quitting the Museveni government in which he had been Foreign Minister and in 1996 launched a presidential bid.

The DP that gave its support to the NRM, enabling the NRM become a strong political force, now found that in 1996 it could not take on the NRM in a general election.

Gen. David Sejusa

Major-General David Tinyefuza was the Minister of State for Defence in 1991. He launched and commanded a counterinsurgency offensive in Acholi and other parts of northern Uganda that year and soon stories of his high-handed and even brutal methods began to trickle into the public domain.

Tinyefuza (today known as Sejusa) regarded all this as a necessary task, wiping out primitive anti-government forces, remnants of the same UNLA army the NRA had defeated in 1986.

By 1996, though, Tinyefuza was a disillusioned man. He announced that the army was being poorly run and he was resigning from it. A much-followed public court hearing after the army refused to retire him made Sejusa the first celebrated figurehead of growing disenchantment with the Museveni regime.

A few years later, Tinyefuza shocked the country by making an about-turn and returning to the NRM government. In 2013, his individualism having returned, he fled into exile in London saying he was on a list of senior government officials whose lives were in danger because they opposed the rumoured plan by President Museveni to install his son, Brig. Muhoozi Kainerugaba, as his successor in power.

Kizza Besigye

In 1989, Besigye was the National Political Commissar. Late that year, the then national assembly called the National Resistance Council voted to extend the term in office of the NRM.

Originally in 1986, the NRM had pledged that it would be in power for only four years until 1990, then call a general election.

Like most NRM leaders, Besigye supported the extension of the NRM as well as the ban on official political party activities.

In 1991, an activist wing of the Democratic Party called the DP Mobilisers’ Group disagreed with the curb on party activities and called rallies to protest this ban.

The police was called in to break up a major rally at the City Square in Kampala. Besigye was the Minister of State for Internal Affairs.

Besigye, like all human beings, could not possibly have foreseen the consequences of this.

In 1999, Besigye wrote a 14-page document outlining what he felt was the serious loss of political direction by the NRM government. Besigye announced he was leaving the NRM and in 2000 launched a presidential bid.

The loss of direction he had described in 1999 became a personal reality for him. The state machinery was unleashed on Besigye. He was harassed and after the 2001 election, fled into exile in South Africa.

On his return in 2005, the harassment by the state resumed with even greater ferocity than in 2001 and has continued for Besigye over the last ten years.

Besigye had been unable to see in 1991 that the same state machinery that tear gassed the DP Mobilisers’ Group would one day turn on anyone who held to the same views as the DP Mobilisers, including him.

Mugisha Muntu

He was appointed the army commander in 1989 and served in that role until 1999. During that ten-year period at the helm of the army, he did not publicly mention anything wrong with the army or the NRM government.

International human rights reports and a number of local ones frequently mentioned atrocities and other abuses of human rights by the army and named individual officers.

The army when deployed in the neighbouring Democratic Republic of Congo was implicated in a massive looting of timber, gold and other resources, and yet life went on for Muntu.

In the early 2000s, like a growing number of NRM figures, Muntu came out publicly to criticize the Museveni regime of which he had been an integral part and later joined the opposition FDC party which he currently heads.

Muntu has had several encounters with the police during his attempts to hold rallies or appear on upcountry radio stations.

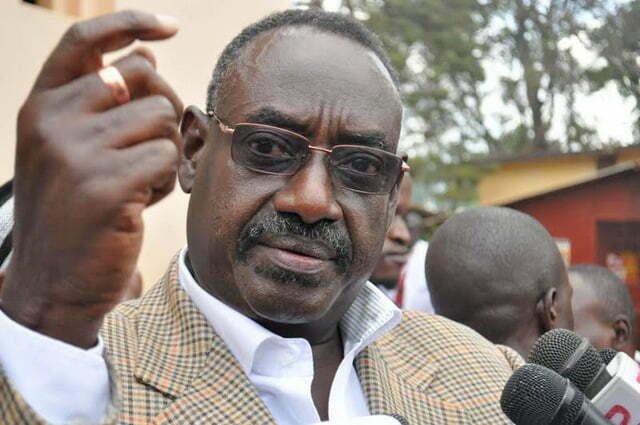

Amama Mbabazi

Unlike Besigye, Sejusa and Muntu, Mbabazi’s association with Museveni went back to the early 1970s during the anti-Amin struggle. After the NRM came to power in 1986, he became central to the NRM’s military and intelligence establishment, holding offices from the director-general of foreign intelligence to becoming Minister of Defence, then Minister of Security.

Also, unlike Muntu, Sejusa and Besigye, although he is presently at odds with Museveni, Mbabazi still affirms his faith in the NRM, says he is still an NRM member, and only announced he would seek the presidency in 2016 as an independent candidate when he was essentially blocked from contesting within the NRM by the party.

Mbabazi was stopped from going on to Mbale in July to hold a consultative meeting, with the police quoting the public order management act that Mbabazi himself pushed through parliament.

His public rallies in Soroti and Jinja were also broken up by the police and teargas fired at his supporters.

In defence of the law, Mbabazi insists that it is still a valid and good law but is being misapplied by the state and the police.

The lesson in this is important for the political class and for the country’s current and future leaders.

History always has a way of making a mockery of mankind. Power, even when it seems invincible, is always weak and can vanish overnight.

When taking part in a political process, a political leader must always think beyond the present and into the distant future. An unprincipled alliance created today, such as the DP with the NRM in 1986 based on restricting the very democratic process that the NRM claimed to have fought a costly war for, can later work against those who enter it.

Secondly, before any leader seeks political office, he or she must read widely about the state and the law and what a state stands for. A political leader must be able to distinguish between a present regime or government and the state.

Laws must be formulated with the benefit of all in society as their main goal. They must seek to be fair to all and must be rigorously applied to all and consistently.

President Museveni and the remaining NRM leaders in power should bear in mind these examples and examples of former heads of state in Africa who could not foresee that one day they would leave power and leave their families at the mercy of the laws created by the all-powerful leader.

The moral is that every leader should have an interest in the creation of laws that are fair to every citizen, including their political rivals. As one is spearheading the passing of a law, especially the kid that usually affect freedom of expression or political activity, one must put themselves in the shoes of the opposition parties and activists the law has in mind before one passes the laws. That is the only basis for one to feel secure.

Often, as history shows, today’s incumbent could be tomorrow’s opposition.